Erle Stanley Gardner

B+

If someone asked people to name the most famous fictional American detective of all time, Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason would get quite a few votes (even though Mason wasn’t technically a detective). If you took that poll 60 years ago, Mason would have been number one. Gardner’s Perry Mason books are still popular, with reprints frequently issued. And the vintage TV series with Raymond Burr still attracts a lot of viewers (as did a more recent HBO revival). The primary reason is Gardner’s style, with lots of dialogue, bizarre plots, and a core set of likable characters. The Case of the Rolling Bones, first published in 1939, is a fine, albeit rather complicated, example of the Mason series.

Perry Mason’s books almost invariably have two things in common. First, Mason’s client is on trial for murder, with the state having built an apparently ironclad case against them. Second, they are innocent (a fact Mason notes with amusement when he boasts to the judge at the novel’s end). In Rolling Bones, the client is wealthy Alden Leeds, who struck it rich in the 1906 Klondike Gold Rush. Leeds has been blackmailed by his

girlfriend’s brother. The man claims to have evidence showing Leeds murdered his former Klondike partner years earlier and then stole all the gold. Naturally, the blackmailer winds up dead, and Leeds was seemingly sharing a dinner in the victim’s apartment when he died.

Rolling Bones is a classic example of the so-called “fair play” mystery, in which the author reveals all the clues Mason and the reader need to solve the murder. This task is more difficult for a writer like Gardner, whose minimalist writing style avoids unnecessary details. But he does so brilliantly here. When I first read the passages where Gardner revealed the critical clue, I felt something was wrong with the author’s description. However, I couldn’t put my finger on it until Mason revealed it to the court and the killer on the witness stand in one of his famous “gotcha” moments. While Gardner’s style is minimalist, his plotting isn’t. As the Cast of Characters page indicates, Mason and the readers have a lot of characters to keep track of, several of whom have multiple identities (in the physical, not the psychological sense). Readers may sometimes have difficulty separating what Mason wants the police to believe and what he actually believes at a particular time. However, readers who can bear some momentary confusion will get a reward at the end when Mason ensnares the killer.

Erle Stanley Gardner was an accomplished trial attorney when he started the Perry Mason series and a champion for social justice at a time when the constitutional rights we take for granted today were almost non-existent. Gardner uses Mason several times as a mouthpiece for the author’s views about the justice system. For example, in the first chapter of Rolling Bones, Mason talks about the type of clients he prefers: “I don’t like rich people. I like poor people… Rich people worry too much, and their problems are too damn petty. They stew up a high blood pressure over a one-point drop in the interest rate. Poor people get right down to brass tacks: love, hunger, murder, forgery, embezzlement—things a man can sink his teeth into, things he can sympathize with.” Considering Leeds’s wealth, that statement proves somewhat ironic in this case.

Gardner also used the Mason books (and, later, the TV series) to educate readers about the justice system. Most Americans in 1939 were unaware of how trials were conducted, and Gardner usually gave pointers in his early books. In Rolling Bones, he discusses how the prosecution must establish a case against the defendant in a preliminary hearing. (Non-spoiler: they don’t do so here.) In the Leeds case, the victim’s actual identity was an issue, and the district attorney and Mason discussed with the judge what the prosecution must do to establish it. This lengthy discussion would be unnecessary at an actual trial with experienced counsel. But these details could be fascinating for lay readers, even more so in 1939 than today.

Rolling Bones also has an interesting subplot in the first few chapters that’s relevant today. Leeds’s relatives commit him to a mental institute by claiming the 70-year-old man has dementia. One relative drives the unknowing Leeds to the facility, where two large nurses grab him and take him inside. When Mason learns about it, he gets a habeas corpus hearing where he shows how flimsy the “documentation” of Leeds’s dementia actually is. While much has changed in the 85 years since the book was written, the issue of involuntary guardianships and conservatorships for possibly mentally unfit people remains a hot topic today.

Rolling Bones is also a time capsule allowing modern-day readers a look into the social mores of the pre-World War II era. From a legal standpoint, some tactics both the district attorney and Mason use would get sharp ethical condemnation today (and would earn the prosecution a reversal if done in an actual trial). At the book’s conclusion, Mason and the judge discuss to what extent the ends justify the means of achieving justice. Some of Mason’s other actions are eye-opening for different reasons. He and Paul Drake smoke constantly, and Mason even keeps a humidor on his desk with four different popular brands of cigarettes for visitors. The book also contains some highly outdated references and descriptions of various female characters that some readers may find offensive.

After I read The Case of the Rolling Bones, I watched its dramatization as an episode of the Perry Mason TV series. The TV show was good, but the book is better. The mystery is more complex and will please most genre fans, even if they don’t figure out the killer. And Earl Stanley Gardner’s style makes for a fast-paced, enjoyable read. Because of the plot complexity, newcomers to the Mason series may want to try another book first. However, those who enjoy the series will want to roll along with The Case of the Rolling Bones.

Author and historian Richard Senate takes viewers on a tour of Ventura, CA where Erle Stanley Gardner first wrote:

Read other reviews of The Case of the Rolling Bones:

Erle Stanley Gardner was a prolific American author best known for his works centered on the lawyer-detective Perry Mason. At the time of his death in March of 1970, Gardner was "the most widely read of all American writers" and "the most widely translated author in the world," according to social historian Russell Nye. The first Perry Mason novel, The Case of The Velvet Claws, published in 1933, had sold twenty-eight million copies in its first fifteen years. In the mid-1950s, the Perry Mason novels were selling at the rate of twenty thousand copies a day. There have been six motion pictures based on his work and the hugely popular Perry Mason television series starring Raymond Burr, which aired for nine years and 271 episodes, as well as a more recent series airing on HBO.

Author William F. Nolan notes, "Gardner, more than any other writer, popularized the law profession for a mass-market audience, melding fact and fiction to achieve a unique blend; no one ever handled courtroom drama better than he did."

Header Photo: "Riot Radio" by Arielle Calderon / Flickr / CC By / Cropped

Silver Screen Video Banner Photos: pedrojperez / Morguefile; wintersixfour / Morguefile

Join Button: "Film Element" by Stockphotosforfree

Twitter Icon: "Twitter Icon" by Freepik

Facebook Icon: "Facebook Icon" by Freepik

LinkedIn Icon: "LinkedIn Icon" by Fathema Khanom / Freepik

Goodreads Icon: "Letter G Icon" by arnikahossain / Freepik

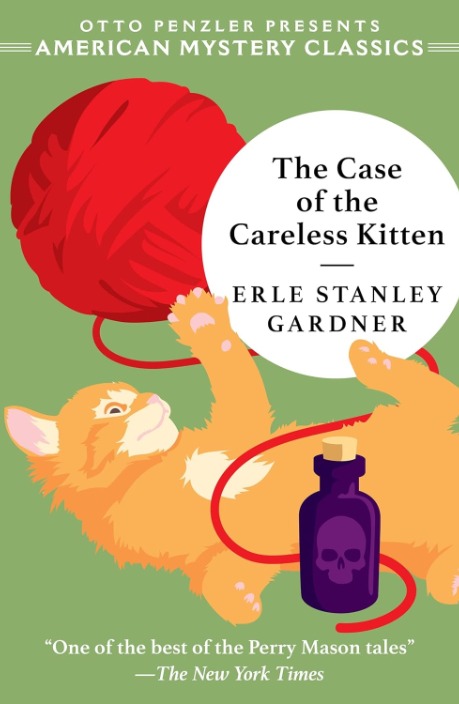

Certain images on this site appear courtesy of Amazon.com and other sponsors of Silver Screen Videos for the purpose of advertising products on those sites. Silver Screen Videos earns commissions from purchases on those sites.

© 2024 Steven R. Silver. All rights reserved.