The history of Blacks in the movie industry is as old as the industry itself. A 29-second silent film entitled Something Good—Negro Kiss from 1898 depicts a black couple kissing and holding hands. Unfortunately, the history of racial prejudice in the film industry is almost as old. One of the most technically accomplished silent films ever made, D.W. Griffith’s 1915 epic, Birth of a Nation, is also one of the most racist. Although many film scholars have written about Birth of a Nation, few studies have explored the many black performers who worked in film, both in front of and behind the camera, since 1898. Ben Arogundade attempts to correct that omission in Hollywood Blackout, a meticulously researched and detailed study of the history of Blacks and other minorities in the film industry.

Hollywood Blackout is primarily a study of Blacks in the film industry, but the author also examines the changing status of other minorities, including Latinos, Asians, Native Americans, and women. Although the book looks primarily at the accomplishments and representation of actors, it also looks at minorities and women in behind-the-camera capacities like directors and screenwriters. The author includes

mini-biographies of seminal figures like Hattie McDaniel, Sidney Poitier, and Denzel Washington. The author concentrates on the Academy Awards, focusing on the presence or absence of Blacks and other minorities among Oscar nominees and winners.

Recognition and inclusion of minorities in the film industry have been agonizingly slow, especially before the 21st century. Hollywood Blackout traces that process, beginning with the advent of the Hollywood studio era after World War I. Many people wanted to appear in the movies. These often untrained and untalented would-be actors, inundated Hollywood, clamoring for any parts they could get in films. Most of those roles are what we now consider extras, although the number of applicants far exceeded the available parts. The flood of would-be extras of all nationalities attracted negative press attention, so the influential Central Casting Corporation was founded in 1925 to organize the hiring process better. The agency started a specialized African American division in 1927, headed by Charles Butler. He soon became the most influential Black in Hollywood. Blacks began to be seen on-screen more often as extras, usually playing domestic servants. Those with comic or musical talent got bigger parts, although often at a humiliating price. Veteran vaudeville performer Lincoln Perry was believed to be the first black actor to get credits billing in a film under the demeaning stage name he was given, Stepin Fetchit.

I consider myself relatively well-versed in Hollywood history, yet almost all of this material was new. I was shocked and fascinated, but not really surprised to learn most of it. Once Hollywood Blackout moved into more recent times, the names and stories became more familiar. The author devoted considerable space to the story of Hattie McDaniel, who rose from Central Casting days as a domestic extra to playing the same type of role in the most expensive film made to date, Gone with the Wind. I knew McDaniel could not attend the movie’s premiere in Atlanta due to the segregation laws in Atlanta at the time. However, I didn’t know that Clark Gable had to personally intervene to get the “Whites only” and “Colored only” signs removed from port-a-potties on the set during filming. I also didn’t know that the Ambassador Hotel in Hollywood, where the 1939 Oscars were presented to Hattie McDaniel and other winners, was also segregated, and the studio had to make special arrangements to allow her and her escort to attend the ceremony. And I didn’t know that McDaniel couldn’t be buried in the Hollywood Memorial Park Cemetery when she died in 1952 because the cemetery, like the Ambassador Hotel and much of Hollywood, was still segregated.

Hollywood Blackout is filled with sad yet fascinating stories like these. The 2002 Oscar ceremonies were especially poignant when Halle Berry and Denzel Washington won the Best Actress and Actor Oscars on the same night and stage as Sidney Poitier was given the Lifetime Achievement Award. The author points out that progress in black representation at the Oscars was often accompanied by significant world events affecting civil rights. McDaniel’s Oscar nomination and victory followed Hitler’s invasion of Poland. Sidney Poitier’s win for Best Actor in 1964 came a few months after Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech and the march on Washington. More recently, in 2017, after the #OscarsSoWhite campaign highlighted the lack of minority acting nominees in the two previous years, nine of the 20 nominees and two winners (Viola Davis and Mahershala Ali) were persons of color. The author shows how the #OscarsSoWhite and similar campaigns came to pass and their effects on the Academy Awards voting practices.

My major criticism of Hollywood Blackout concerns its focus on one highly visible but tiny aspect of minority presence in the film industry… the Oscars. Only 20 actors receive Oscar nominations each year, yet thousands more have successful careers without getting close to an Academy Award. I realize that data from the early days of Hollywood is sketchy, but figures for minority representation in the industry today are readily available. Actors like Dwayne Johnson and Kevin Hart will probably never get Oscar nominations, but they do well financially and at the box office. Yet, after a promising start, “Hollywood Blackout” focuses almost entirely on the presence (or lack thereof) of minorities at the Oscars. The Blaxploitation phenomenon of the 1970s isn’t mentioned (other than Isaac Hayes’s Oscar for the theme from Shaft), and the groundbreaking 1940s musical Cabin in the Sky (directed by Vincente Minnelli with an all-black cast) gets one brief mention. The author finds time to describe the changes in the design of the Oscar statuette over the years and the outfits minority nominees wore to the ceremonies in different years but not significant events in filmmaking that didn’t involve the Academy Awards per se.

Racism and discrimination in Hollywood are less prevalent today than in previous decades, but they still exist. No black director has ever won the Best Director Oscar, although two films with black directors and predominantly black casts (12 Years a Slave and Moonlighting) have won the Best Picture Oscars in the last decade. Hollywood Blackout demonstrates the ugly side of racism in the industry, with depressing, often shocking anecdotes and dozens of pages of interesting facts and figures. The author has taken his detailed research and presented it in a form that’s both easily readable and compelling (including a yearly chronology of significant milestones). I recommend Hollywood Blackout for those interested in the film industry or current events.

NOTE: The publisher graciously provided me with a copy of this book through NetGalley. However, the decision to review the book and the contents of this review are entirely my own.

In this clip, author Ben Arogundade discusses Hollywood Blackout with Dr. Denise Nicholson on her Bold Book of the Day podcast:

Read other reviews of Hollywood Blackout:

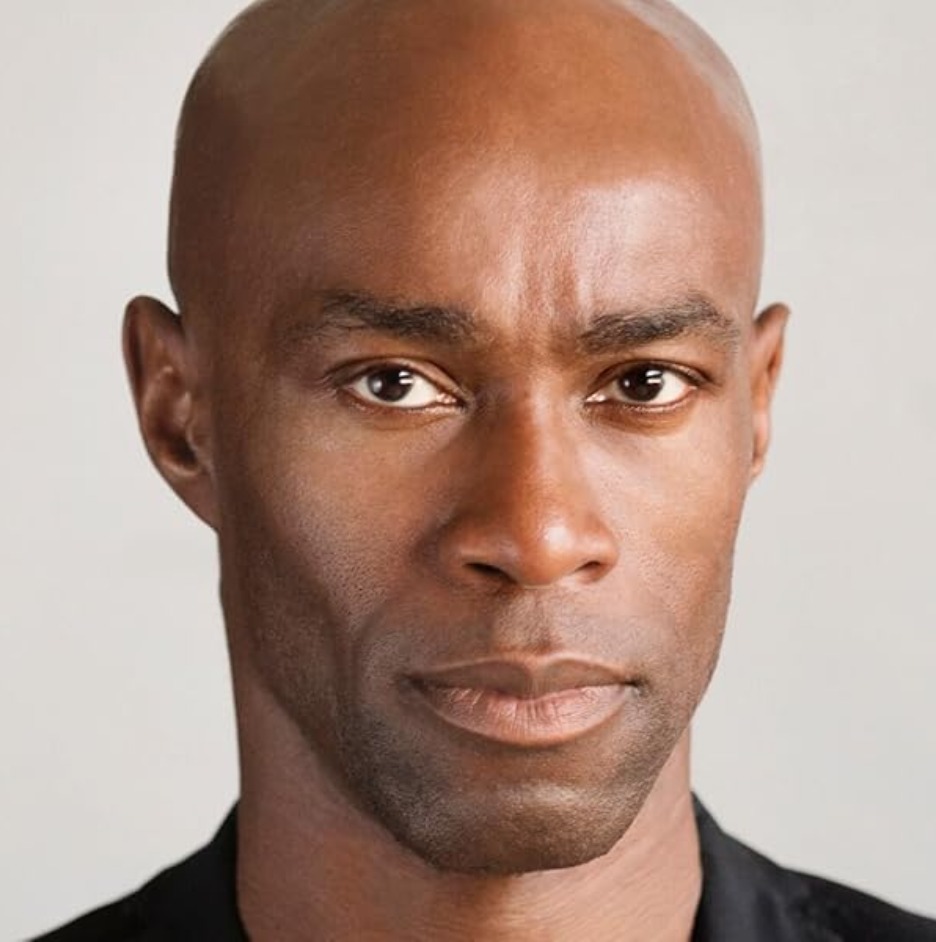

Ben Arogundade was originally trained as an architect, before diversifying into graphic design and journalism. He has written for a range of publications, including The Times, The Telegraph, The Guardian, The Evening Standard, Elle, Marie Claire, and Creative Review.

He has written and edited 12 works of fiction and non-fiction, including Black Beauty and Obama: 101 Best Covers. Black Beauty, which narrated the history of society’s perceptions of the aesthetics of people of color, was honored by the New York Public Library and became the subject of a three-part BBC documentary. His book, My Terrifying, Shocking, Humiliating, Amazing Adventures in Online Dating, is currently being adapted for television by Channel 4.

Header Photo: "Riot Radio" by Arielle Calderon / Flickr / CC By / Cropped

Silver Screen Video Banner Photos: pedrojperez / Morguefile; wintersixfour / Morguefile

Join Button: "Film Element" by Stockphotosforfree

Twitter Icon: "Twitter Icon" by Freepik

Facebook Icon: "Facebook Icon" by Freepik

LinkedIn Icon: "LinkedIn Icon" by Fathema Khanom / Freepik

Goodreads Icon: "Letter G Icon" by arnikahossain / Freepik

Certain images on this site appear courtesy of Amazon.com and other sponsors of Silver Screen Videos for the purpose of advertising products on those sites. Silver Screen Videos earns commissions from purchases on those sites.

© 2025 Steven R. Silver. All rights reserved.