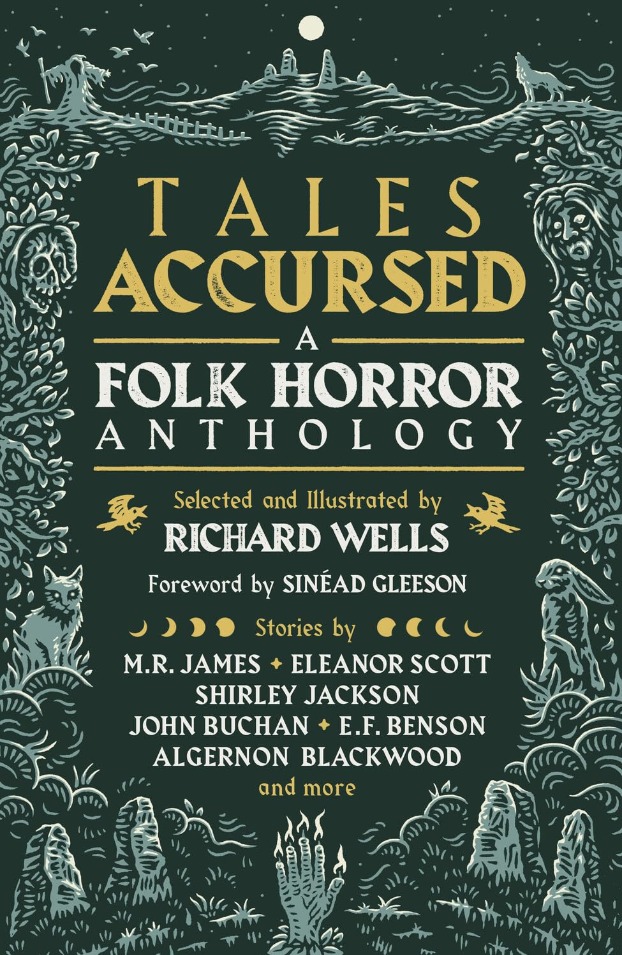

One of our most cherished “literary” traditions is the campfire story. Young people sit around an outdoor fire late at night and swap horror stories, often about killers or monsters on the loose. As someone who sat and listened to these stories in my youth, I can attest they can be very spooky when told in the right way. As the story is told, we keep looking into the darkness to see if something is out there. But in the light of the following day, when we realize we’ve just been sitting in an empty field, the stories often seem silly. Tales Accursed, an anthology compiled by illustrator Richard Wells, is a collection of 16 similar stories with a more supernatural edge. But while a few of them were creepily entertaining, most of them were difficult to follow and resembled the disappointing morning-after landscape from my youth.

The 16 stories in Tales Accursed date from 1870, and most were written before 1930 (and are in the public domain). Even the handful of more recent stories often recount events that occurred decades

or centuries earlier. Some authors, like Algernon Blackwood, Sheridan Le Fanu, John Buchan, and Shirley Jackson, are very well known to horror buffs or literary fans in general. Others are more obscure, some deservedly so. Almost all the stories are set in the British Isles. The plots are simplistic, with few frills and nuances. The stories take place in secluded, gloomy places or on remote mountaintops. They involve ghosts, witches, demons, strange creatures, and pagan religious rituals, almost all occurring at night. The so-called “normal” people who encounter these entities usually come to bad ends or disappear without a trace.

The stories in Tales Accursed have a monotonous sameness to them, just like the campfire stories from my youth. Whether written in the first or third person, most of the tales are simply narratives of myths the author or narrator has heard at one time or another, often from someone else relating what they heard at one time. Second- or third-hand hearsay about things taking place far away isn’t the scariest material, especially if the author abruptly shifts narrators or points of view throughout the story. Further, the speakers often relate their tales in thick dialects, with Gaelic, Latin, or other foreign words or phrases frequently thrown in. As a result, I had difficulty understanding what they were saying, even if I reread the passages several times. I’m still unsure what happened in some of these stories. Needless to say, stories you have to strain to understand aren’t usually the spookiest.

These tales’ age works against them as well. Only five stories were written after 1930, and two were set decades or centuries earlier. Most stories first appeared in various British monthly magazines of the era (the same publications in which early Agatha Christie short stories appeared). These tales tend to be lengthy, with much empty language (authors often got paid by the word). They wouldn’t escape the typical editor’s red pen today. The verbosity and overly ornate language disguise the fact that most folk tales are basic stories in which few events actually occur.

Some stories are good, especially those that place the central character inside the story rather than just hearing it recounted. The narrator of John Buchan’s “No-man's-Land” takes a hiking trip to the Scottish Highlands. He ignores the stories of strange creatures lurking in the woods until he gets lost. The narrator recounts the danger he faces going through foggy moors with treacherous footing and the even greater danger he encounters when he meets the creatures. Similarly, in “The Temple” by E.F. Benson, the narrator and a friend go on a holiday to Cornwall to enjoy golf and study the plentiful ancient ruins to be found. What they find is that the house they rent sits in the middle of what once was a pagan temple that practiced human sacrifice. Genre fans will appreciate what happens next far more than the narrator and his friend did.

Two of the more recent stories are among the best in the anthology. H.R. Wakefield’s “Woe Water” first appeared in “Weird Tales” in 1950, when horror writing had developed somewhat. It’s the diary of a man who claims his wife accidentally drowned, despite considerable evidence to the contrary at a coroner’s inquest. He buys a house that has a lake on the property, where several locals committed suicide over the years by drowning themselves. The narrator’s grip on reality and sanity quickly unwinds as the story progresses.

“Lisheen” by Frederick Cowles isn’t actually scary, but it will leave modern-day readers with a highly queasy feeling. The story was written in the 1940s but didn’t appear in print until 1993, over 45 years after the author’s death (for reasons I can guess based on the contents). Its central character is a 17th-century minister whose story is revealed in bits and pieces in Church records re-discovered in the 20th century. The minister witnesses the birth of a local girl whose mother dies in his presence. Also on hand for the event is the baby’s father, a demon visible only to the minister. Despite this vision, the minister adopts the girl, whom he names Lisheen. She’s bright and attractive but, at age six, starts removing her clothes at night and going to the ancient ruins on top of a nearby mountain. The minister follows and watches the ensuing rituals, year after year, until Lisheen turns 17, and he decides to marry her. This story would have been highly distasteful in the 1600s, the 1940s, or 1993. Today, it’s even more so, but it holds a creepy fascination for some and extreme disgust for others. Anyone reading Tales Accursed is forewarned.

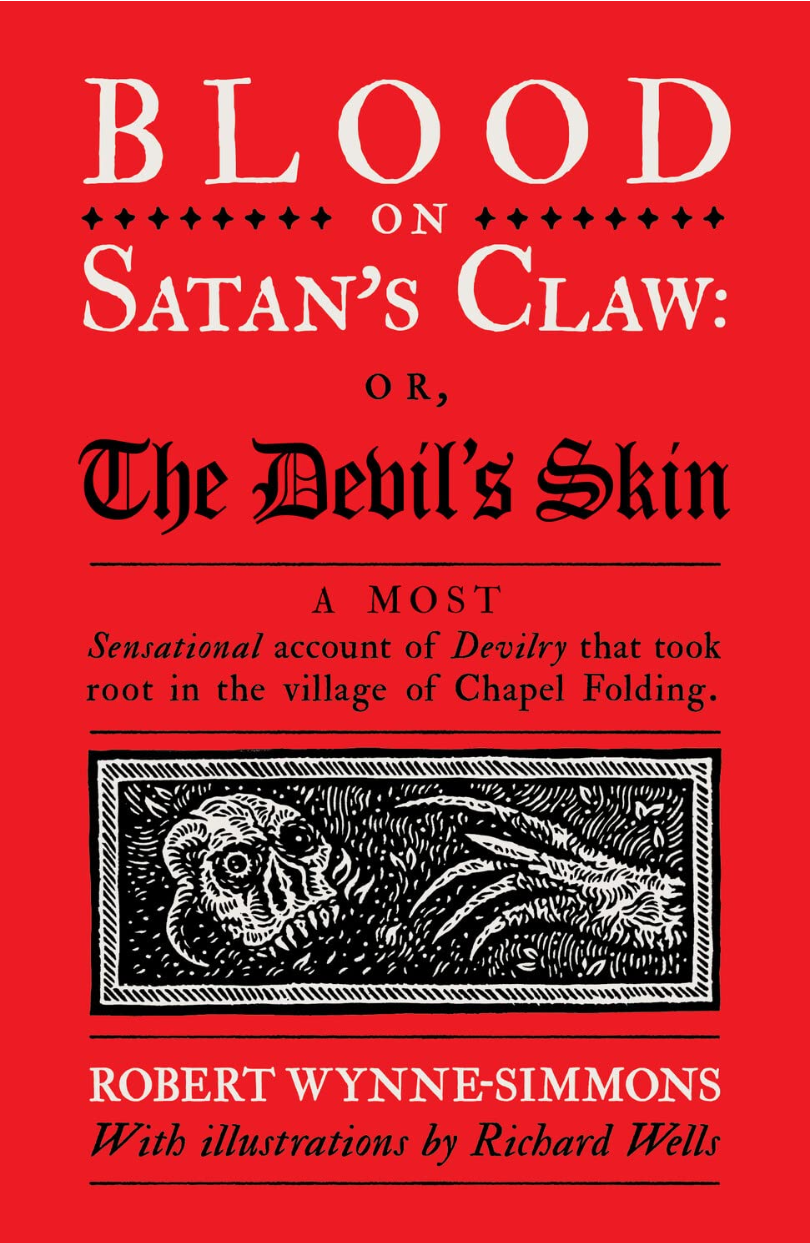

Although the stories in Tales Accursed are highly uneven in quality, Richard Wells, an accomplished illustrator, provides woodcut-style drawings that precede each story and hint at the tale’s contents. These drawings complement the anthology’s best stories and make the others more tolerable. I highly recommend them to graphic horror novel fans and other dark art lovers.

However, I can’t recommend Tales Accursed. About one-third of the stories are entertaining, while many others are boring at best and nearly incomprehensible at worst. Further, they suffer from a sameness that makes binge readers feel they are repeatedly rereading the same stories. Recounting ancient folk horror successfully in a modern-day setting requires a deft touch that most of these authors cannot demonstrate. Accursed are they who waste their time making their way through Tales Accursed.

NOTE: The publisher graciously provided me with a copy of this book through NetGalley. However, the decision to review the book and the contents of this review are entirely my own.

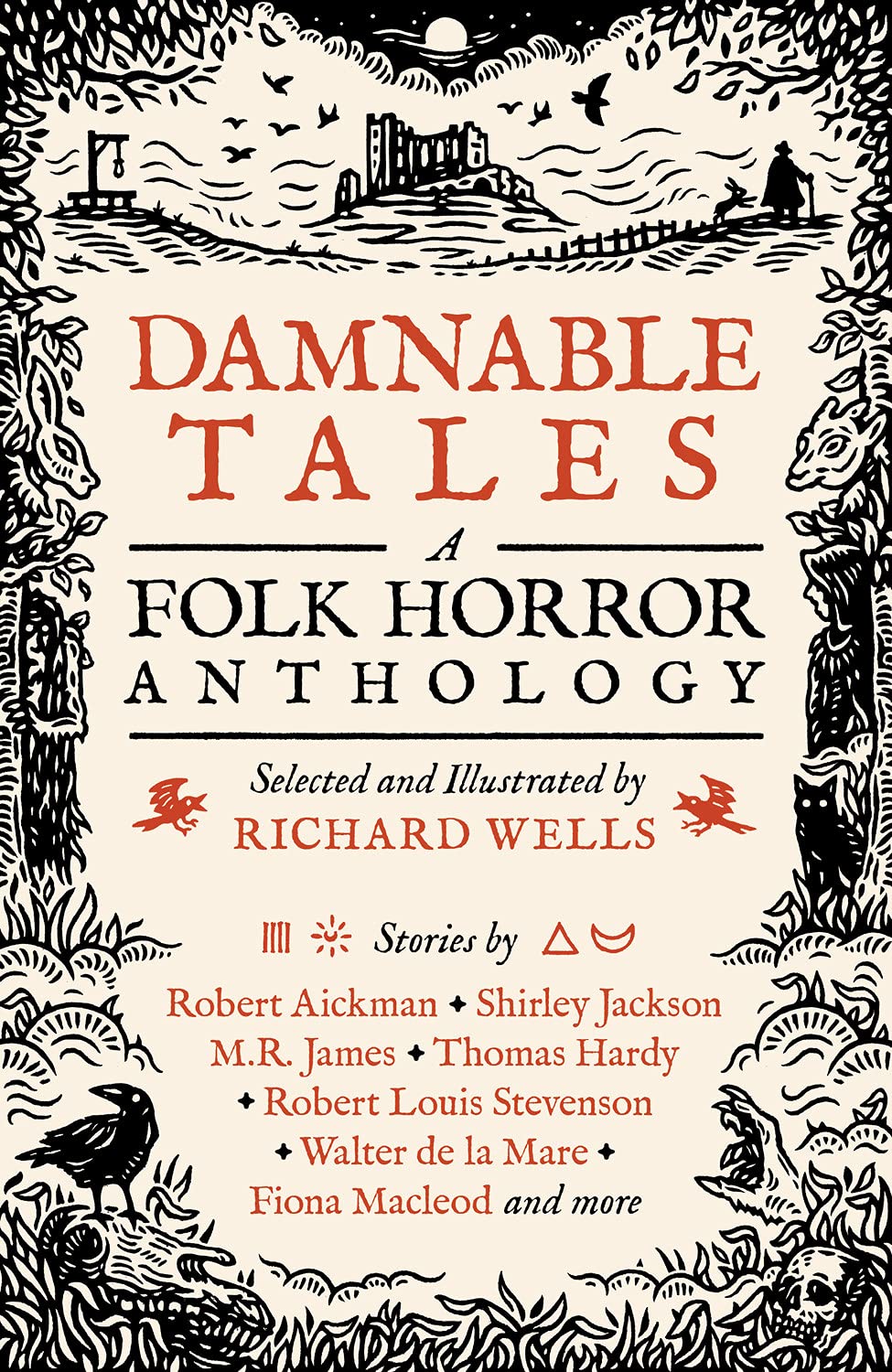

In this clip, Tony Walker of the Classic Ghost Stories podcast discusses Richard Wells' previous folk horror anthology :

Read other reviews of Tales Accursed:

Richard Wells is a British illustrator and graphic designer, who has primarily worked in the television industry. Wells has provided graphic props for the likes of Poldark, Sherlock, Doctor Who, and the BBC adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Outside of his television work, he makes and sells his own darkly folkloric artwork, often lino cut and printed by hand. He is also the editor and illustrator of folk horror anthologies Damnable Tales and Tales Accursed.

Header Photo: "Riot Radio" by Arielle Calderon / Flickr / CC By / Cropped

Silver Screen Video Banner Photos: pedrojperez / Morguefile; wintersixfour / Morguefile

Join Button: "Film Element" by Stockphotosforfree

Twitter Icon: "Twitter Icon" by Freepik

Facebook Icon: "Facebook Icon" by Freepik

LinkedIn Icon: "LinkedIn Icon" by Fathema Khanom / Freepik

Goodreads Icon: "Letter G Icon" by arnikahossain / Freepik

Certain images on this site appear courtesy of Amazon.com and other sponsors of Silver Screen Videos for the purpose of advertising products on those sites. Silver Screen Videos earns commissions from purchases on those sites.

© 2024 Steven R. Silver. All rights reserved.